- Subscribe to RSS Feed

- Mark as New

- Mark as Read

- Bookmark

- Subscribe

- Email to a Friend

- Printer Friendly Page

- Report Inappropriate Content

In a recent blog post, I described Renderscript - the new high performance 3D graphics API for Android. To refresh your memory, Renderscript is

- a new API, published with the Honeycomb API release

- made up of a "computing" API, and a "rendering" API

- intended for programmers who want to coax the last ounce of performance from their hardware

- accessed using a C-based scripting language

The earlier post showed how to compile and run the sample Renderscript code included with the Honeycomb SDK. This blog post reviews the source files for one of the Renderscript samples, and explains how a Renderscript app is composed.

When analyzing something new, it's usual to start with the simplest example and proceed from there. In the case of Renderscript, the simplest example is the "Hello World" code, provided as one of several sample apps. No one would actually use Renderscript in real life to put a string on the screen, but it's a great way to look at the files needed for a minimal example.

Renderscript source code

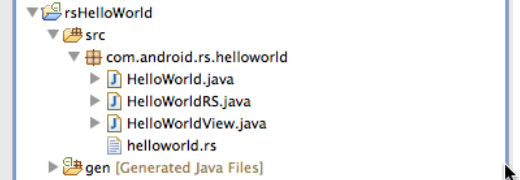

After you import the sample code into Eclipse (described in the earlier blog post), you will see four source files.

Figure 1: Four source files make up the Hello World Renderscript example.

You keep your Renderscript scripts in the src folder of the project. A Renderscript file looks like C code, although with some special pragmas and names. Look at helloworld.rs first -- this is the actual Renderscript script for the example. Here's that .rs file, stripped of pragmas and most comments:

#include "rs_graphics.rsh"

int gTouchX;

int gTouchY;

void init() {

gTouchX = 50.0f;

gTouchY = 50.0f;

}

int root(int launchID) {

rsgClearColor(0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f); // set background black

rsgFontColor(1.0f, 1.0f, 1.0f, 1.0f); // set font white

rsgDrawText("Hello World!", gTouchX, gTouchY);

return 20;

}

If you're comfortable with C, you'll be immediately comfortable with the syntax and appearance of Renderscript. [You'll probably also notice that the rsgClearColor() call should be as below, for example. I'm not sure what it means to set the alpha value of the background to anything other than fully opaque. Possibly it means nothing, if the alpha channel is ignored for backgrounds. (But if it is ignored, why is it a parameter?) ]

rsgClearColor(0.0f, 0.0f, 0.0f, 1.0f); // set background opaque black

The init() function is for one time set-up. It is called once for each instance of this Renderscript file that is loaded on the device, before the script is accessed in any other way by the Renderscript runtime.

The root() routine is the equivalent of main(). Root() is called for each frame refresh for the surface it is being rendered to. The return value, 20 here, tells Renderscript runtime approximately how many milleseconds should elapse between redraws. So the frame rate here is about 50 fps.

#include header files

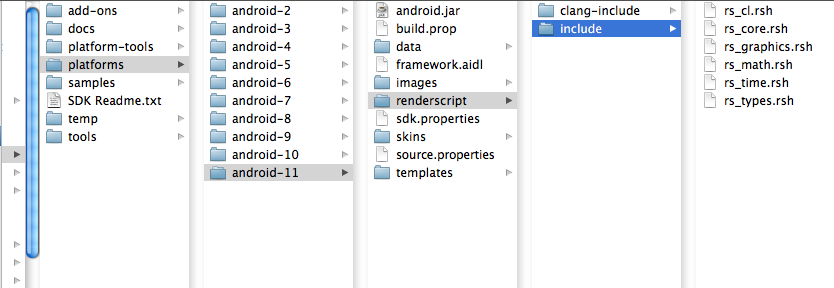

The "#include" brings in the header file for the Renderscript graphics. You can find that rs_graphics.rsh file in your SDK, in the folder platforms/android-11/renderscript/include, along with 5 other .rsh ("Renderscript header") files. In an unexplained break with C convention, these other five files are included automatically when needed. The 6 .rsh files together provide the namespace for typedefs and the functions that you can call in your Renderscript scripts.

If you want to try modifying this script, there's an rsRand() function you can use, in rs_math.rsh. You could use that to pick random values for the font color. Or animate the text on the screen by moving a small amount in each frame.

Figure 2: Review the six rs_*.rsh files in the SDK to see the names in the Renderscript API.

As its name suggests, rs_graphics.rsh contains the declarations of about 30 graphics-oriented routines in the native Renderscript libraries. These are operations like rsgClearColor() to set a rendering surface to a specific color, and rsgDrawMesh() to draw a mesh of geometry.

The other 5 .rsh files contain declarations of math and utility functions. The math functions are overloaded so they work on both scalars and vectors. There is a clang-include directory containing a score or so C header files, also relating to math and other supporting features to use in your scripts.

Compute Scripts and Graphics Scripts

It is perfectly possible to use Renderscript for intensive number-crunching that is unrelated to graphics (e.g. weather modeling). You do this by using the math library, and never calling any rendering routines. There are thus two kinds of Renderscripts:

- a compute Renderscript only does number-crunching and no rendering

- a graphics Renderscript does graphics rendering plus any calculations needed to support it.

For both kinds of script, the basic model is to do all your memory allocation in Java, and then hand all the data to Renderscript for crunching and rendering. You don't do any memory allocation in Renderscript. This limitation allows Renderscript to allocate processing units freely, on CPU cores or the GPU, as available. This ensures that maximum resources are brought to bear on CPU-bound programs, and you get the highest possible performance from your hardware.

The "silicon fungibility" (capability for mutual substitution) brings with it two restrictions. GPUs don't have the same hardware support for debugging that CPUs have. So you can't set breakpoints and debug your scripts using the debugger. Second, Renderscript cannot call any C libraries or code, because these functions assume they running on a CPU, not a GPU. For the same reason, you cannot run Renderscript programs in the emulator.

How your Renderscript source interfaces to Android/Java

Renderscript programs start off with an Android project created in Eclipse. The Android code manages the Activity lifecycle.

When you build a project containing Renderscript, the build system automatically generates some Java "glue" code that makes the Renderscript objects visible to your Android Java code, and vice versa. The generated code provides get/set routines, allowing Java to see and use Renderscript variables like gTouchX and gTouchY in the sample. The generated code can be seen in your project's gen directory, but you probably never need to look at it.

The prohibition on calling C, mentioned above, rules out calls to malloc, calloc, and other C-based dynamic memory management (except allocation on the stack presumably, if you can do it without calling alloca()). Your scripts will request memory by using the rs_allocation type, defined in the rs_types.rsh header file. This will call back into the generated Java "glue" code, and get the memory using the class android.renderscript.Allocation. All dynamic memory management is done within Java and Android.

Other Source Files

There are three other files in the hello world source folder. They are quite brief, so I'll just list their purpose here, and invite you to review the source code at your leisure.

- HelloWorld.java -- this is very close to the "hello world" template that Eclipse gives you. The only significant addition is the instantiation of a HelloWorldView object in onCreate(), which is then set as the content view

- HelloWorldRS.java -- this file is the renderer. Rendering is the last step in the graphics pipeline, turning the 3D model into a 2D raster representation on the screen. The code reads in the helloworld.rs Renderscript (accessing it as a project resource), and binds it to a Renderscript GL object. That causes the init() and root() methods of the script to be called, and away we go.

- HelloWorldView.java -- this file creates a surface (a memory buffer that can be drawn on), and passes it to the init() routine of HelloWorldRS. As the only View in the Activity, this class gets onTouchEvents. It passes the X,Y coordinates to HelloWorldRS.java, which in turn calls the "glue" code to pass them to your script.

Other References

There aren't a lot of Renderscript articles at the time of writing (March 13, 2011). After you've read this post, and want more details, here are the two references I used:

http://developer.android.com/guide/topics/graphics

http://developer.android.com/reference/android/ren

If you have any suggestions for improving or extending this blog post, to make it a more useful or complete introduction to Renderscript, please post them as a comment below. I will update the article (or post a new one) to include the best suggestions. Cheers,

Peter van der Linden

Android Technology Evangelist